Reflections on running spaCy: commercial open-source NLP

As more and more people and companies are getting involved with open-source software, balancing the expectations of an open community and a traditional provider vs. consumer relationship is becoming increasingly difficult. Are maintainers becoming too authoritarian? Are users becoming too demanding? Are large companies selling out open-source?

In this post I’ll share some lessons we’ve learned from running spaCy, the popular and fast-growing library for Natural Language Processing in Python. I’ll also give you my perspective on how to make commercial open-source work for both users and developers.

Unpacking open-source

Looking at the open-source ecosystem as one giant space with a fixed set of rules and best practices can be problematic and frustrating. It’s frustrating for maintainers of private projects, who end up overwhelmed by the flood of bug reports and often demanding support requests. It’s frustrating for companies who open-source their tools and are suddenly expected to get as many contributors involved as possible. And it’s frustrating for users, who keep getting told to “submit a PR or shut up”, and are struggling to decide which project to adopt and trust.

Most open-source projects roughly fall into one of three categories:

Private“I made a thing and it’s over here.” | Community“Let’s make a thing together.” | Commercial“We made a product and it’s free.” | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintainer Control | high | low | high |

| Maintainer Responsibility | low | medium | high |

| User Responsibility | high | high | low |

Private projects are usually maintained by one person making most of the decisions, but bearing little responsibility. After all, it’s just a person sharing their code or showcasing their work, hoping it might be useful to others. Community projects tend to make decisions collectively: maintainers take responsibility for the software, but ultimately, users are expected to get involved, instead of only making demands. In return, they get a say in the project direction.

Commercial projects on the other hand generally stay more centralised: maintainers often run a business related to their software and retain more control over their project, while investing more resources and expecting less of their users. Even projects by very large companies like Google and Facebook with sizable developer communities roughly follow the same line of thought.

A case for centralised, commercial open-source

In many ways, spaCy is a pretty typical commercial open-source project. It’s developed and maintained by mostly two people – Matt and me. spaCy puts our work in front of many developers, which has allowed us to bootstrap our company Explosion AI independently through consulting work while keeping our software free.

spaCy’s strength is that it’s easy to use, fast and opinionated. There’s only one implementation of each component, and we’re trying to make it the best possible one. At the same time, the core of spaCy is inherently hard to contribute to. It’s fast because it’s written in Cython, a relatively niche language. The API is easy to use because it’s cohesive and was mostly written by a single author.

All of this makes spaCy a good fit for production use, and we’re excited to see more and more companies using it to power great products. But growth also comes with responsibility. By making the choice to adopt our open-source software, our users are offering us a large amount of trust upfront. We’re asking for that trust, so we need to keep up our end of the bargain. If something is broken, we need to fix it. If we rely on users to report problems, we better make their experience pleasant. If we’re encouraging people to use spaCy in production, we are responsible for making it work. And if we want to keep spaCy cohesive and maintain attention to detail, we need to take the lead.

As we’re moving into a phase with more options for contributions, we want to encourage them where they make the biggest difference: language data, interoperation, tests and documentation. After we provided more docs and refactored our website’s markup language, we saw a big increase in small pull requests – from fixing minor typos in the docs (I admire everyone who goes out of their way to do this!) to adding tokenizer exceptions for Bengali or Hebrew.

Our community consists of people with very different backgrounds and motivations – developers who’ve been working in computational linguistics since before it was cool, deep learning engineers training models with text input, data scientists and digital humanities researchers, mobile app developers working on their first bot and computer science students looking to get started. (For the record, my background is front-end development, marketing and linguistics.) AI is not a field of homogenous skills and experiences, and if we want to build great software, need to adapt the way we think about community-driven development.

Challenges for open-source NLP

One of the biggest challenges for Natural Language Processing is dealing with fast-moving and unpredictable technologies. Most open-source development follows a basic assumption: There’s a bug, and there’s a fix. There’s a feature, and there’s an implementation. The quality of the code may vary and there are always trade-offs. But ultimately, there’s a path, and there’s a goal. This is a lot less true in AI or NLP.

Since spaCy was released, the best practices for NLP have changed considerably. This also means that the library has had to change a lot. For instance, dependency labels used to be much more relevant – now, our biggest focus is getting spaCy up to speed with deep learning. However, new features and enhancements are still based on very subjective assumptions about how people are going to do NLP in the future. And it’s not only about code. There’s another component that’s just as important: statistical models.

In the past, spaCy’s models had to be downloaded via a server maintained by us. Although they played a huge part in spaCy’s performance, they were mostly hidden away from the user. This was problematic – black-boxing technology is pretty much the opposite of what we want to stand for. But how do you “open-source” large binary data?

In spaCy v1.7, we finally introduced a new way of loading models, by wrapping them as Python packages that can be installed via pip. All files are also available attached to individual GitHub releases, containing more information on the model’s capabilities, license and data. We’ve also included a model packaging tool in spaCy’s CLI so users can package their own models.

Aside from the obvious advantages, like native versioning and pip installation, model as packages send a much more reasonable message: A model is a component of your application, just like any other dependency. In reality, there’s not one “the model”. There can be many different ones with different capabilities, that will produce very different results depending on what you do with them. You can train your own models from scratch, or update existing ones. And you can package and share your models with the community, just like we do.

Giving projects a voice

Whether you want it or not, your project will have a voice. Yours. This includes everything you say and do – from documentation you write to issues you answer. If a project sends mixed messaging, it causes confusion and conflicts. The website says “Use our software!”, while the maintainers say “PR or GTFO”. The community guidelines say that “there are no stupid questions, just stupid answers”, while the maintainers mock their user’s issues on Twitter. Being rude is not quirky, and it doesn’t save you any time or money either. People will not appreciate your work more if you put them down.

This is also important to keep in mind when talking about diversity in open-source and building an inclusive community. It’s not enough to simply adopt community standards and state that “everybody’s welcome”. If this is what you believe in, it also needs to be reflected in the overall messaging of your project. (GitHub’s Open Source Guide has a nice summary on this topic.) There’s also a difference between giving detailed guidance, and enforcing strict rules. People are less likely to invest time and contribute to a project if there’s a high potential of “doing things wrong” — either due to lack of clarity, or arbitrary and overly rigid rules where every deviation will be scrutinised.

Another root cause of mixed messaging is a lack of predictability. Users and contributors should know where the project is going – even if ultimately, the maintainers are going to be the ones making the decisions. Unreliable startups and their amazing journeys have made people wary of being lured in with big promises, only to be let down.

One of our goals for spaCy is to focus on communicating our plans and ideas more openly. This is one of the downsides of being such a small team: a lot of decisions happen in one or two heads, which deprives the community of insights into the process. Some of our decisions have been more controversial than others, but no matter how much thought we put into them, it becomes irrelevant if we don’t talk about it publicly. (Docker’s recent fiasco is an example of how this can go very wrong and cause a lot of frustration.)

Avoiding issue tracker bankruptcy

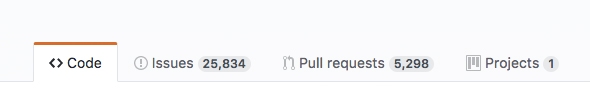

By running spaCy in a centralised way, we accept that we have to be the main source of support for now. This is hard, and we’ve not always been doing a great job at this. It’s easy to get get stressed out when seeing the issue count go up and falling behind on maintenance. We’ve all seen it before in other projects: issues keep piling up and the maintainers, unable to keep up, eventually declare issue tracker bankruptcy.

We try to label issues as they come in, even if we don’t have time to reply or get to the bottom of them. Of course, reorganising the reports won’t actually fix any bugs – but it makes it much easier to work through them systematically. It also sends a message to our users: your report has been acknowledged and we’re on it.

As we tackle larger improvements to the library, we make a list of related

issues and merge them all into one master issue that summarises the problem and

planned solution. This lets us communicate our plans and add valuable

information, while reducing overhead – and closing a bunch of issues at once! If

the master issue is self-contained and easy to fix, we’ll add a help wanted

label to offer it for contributions. If somebody else wants to take it on,

they’ll already have all the instructions they need, plus a handy list of

related issues for reference.

Another tool that has made a huge impact is Gitter, a chat client that integrates with GitHub. With the Gitter widget added to our website, users can even chat while browsing the documentation. It’s a great way to connect with our community, find out what people are working on, answer simple questions and discuss topics related to spaCy and NLP. The more we learn about people’s workflows and what they’re trying to achieve, the better we’ll become at anticipating what’s needed to solve future NLP problems. After all, we’re not just fixing bugs here.

With almost 400 members, we don’t always get around to answering every question. But it also means other people can step in. It always makes me happy to see community members helping each other – whether it’s fixing a bug in someone else’s code, or exchanging contact details to work on language models together.

Monetising open-source without selling your docs

We often get asked why we don’t accept donations. While it’s flattering to hear that people like the project and want to support it, we’ve decided to keep a stricter separation between our free software and how we’re making money.

Services like Gratipay, BountySource or Patreon are great for personal projects and offer a quick and effective way of saying “thank you”. So is selling merchandise. But for a commercial project, monetising your user’s gratitude is a pretty bad business model. Ultimately, it comes down to this: Are you a business, or a charity? If you’re not a charity, it’s not even possible for companies to “just give you money”. Instead, you’re asking private people to fund a project so companies can profit from it for free.

For a long time, the predominant idea of monetising an open-source project was offering a commercial version, enterprise offerings, “OSSaaS” or paid support. Even today, some people still seem to believe that those are the only options. The problem is that the incentives here are entirely misaligned. If you’re making money off helping people use your software, you need to be strategic about the help you provide for free. No matter how you twist it, you’ll eventually end up in a deadlock: If your software becomes better and more popular, you’ll lose business, as other people become less dependent on you for services and support. If it doesn’t, you’ll keep losing even faster, as your software is the only source of new customers.

The good news is: If your users like your software, it’s clearly solving a problem for them. If they build a business on top of it, even more so. This gives you a unique perspective on people’s needs and a lot of valuable relationships. What you go on to offer them commercially doesn’t have to be tightly coupled to your open-source project. In fact, it’s often best if it isn’t.

Our users like spaCy because they’re building applications using NLP and want to do this as efficiently as possible. spaCy’s capabilities are all pretty useful in themselves – but they only become really valuable in combination with data. This is what makes open-source NLP and machine learning software different from a lot of other open-source tools. If you’re serious about what you’re doing, you’ll eventually need models that go far beyond general-purpose language models, and you want to train and update them with your own data. Software can help you achieve this – but it won’t do all the work for you.

We believe that our users will get the most value out of tools and data assets they can own and keep. We’re still working on our line of products and I hate talking too much about what we’re going to do, it just makes me impatient. But we hope we’ll be able to keep providing value to our users – both in the open-source library and with product offerings.